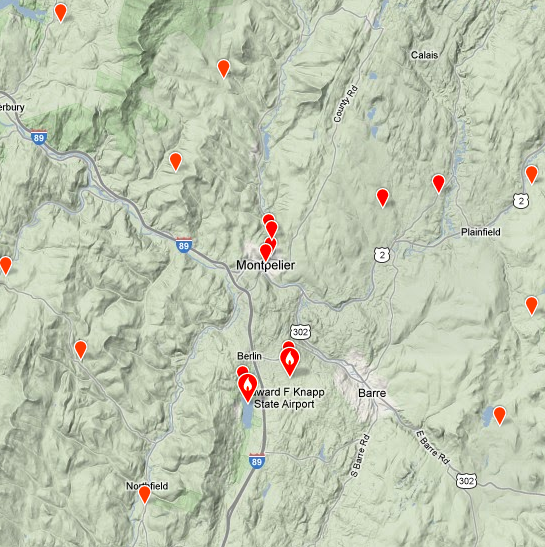

Since we are not traveling to the Southwest this winter, I’ve been giving some thought to doing a low key birding big year. I have no interest in a national effort but at first was thinking about a Vermont big year. I’m gravitating toward a Washington County big year but we’ll see as this year ends and plans for next year firm up a bit.

I’ve read a number of big year books and blogs and enjoy many of the quests, as crazy as they might get. As we know, a big year is an informal quest among birders to see who can see or hear the largest number of species of birds within a single calendar year and within a specific geographical area. A big year may be done within a single US state, a Canadian province, within the lower 48 continental U.S. states, or within the official American Birding Association Area. Here’s some historical information from Wikipedia:

The earliest known continent wide Big Year record was compiled by Guy Emerson, a traveling businessman, who timed his business trips to coincide with the best birding seasons for different areas in North America. His best year was in 1939 when he saw 497 species. In 1952, Emerson’s record was broken by Bob Smart, who saw 510 species.[1]

In 1953, Roger Tory Peterson and James Fisher took a 30,000 mile road trip visiting the wild places of North America. In 1955, they told the story of their travels in a book and a documentary film, both called Wild America. In one of the footnotes to the book Peterson said “My year’s list at the end of 1953 was 572 species.” In 1956 the bar was raised when a 25-year-old Englishman named Stuart Keith, following Peterson and Fisher’s route, compiled a list of 598 species.

Keith’s record stood for 15 years. In 1971, 18-year-old Ted Parker, in his last semester of high school in southeastern Pennsylvania, birded the eastern seaboard of North America extensively. That September, Parker enrolled in the University of Arizona in Tucson and found dozens of Southwestern U.S. and Pacific coast specialities. He ended the year with a list of 627 species. (Before his death in 1993, Parker went on to become one of the world’s most renowned field ornithologists, and the acknowledged leading expert on the birds of the American tropics. He is recognized as an influential birder today.)

In 1973 Kenn Kaufman and another birder, Floyd Murdoch, went after Parker’s record. As recounted in the book Kingbird Highway, both broke the old record by a wide margin. Murdoch finished with 669 in the newly-described ABA area (North America north of Mexico, essentially) and Kaufman had 666. Kaufman set a North American record of 671 species, with the addition of five species that he had seen in Baja California.

In 1973 Kenn Kaufman and another birder, Floyd Murdoch, went after Parker’s record. As recounted in the book Kingbird Highway, both broke the old record by a wide margin. Murdoch finished with 669 in the newly-described ABA area (North America north of Mexico, essentially) and Kaufman had 666. Kaufman set a North American record of 671 species, with the addition of five species that he had seen in Baja California.

Murdoch’s record was broken in 1979 by James M. Vardaman, as recorded in his book Call Collect, Ask for Birdman. Vardaman saw 699 species that year and travelled 161,332 miles (137,145 by airplane; 20,305 by car; 3,337 by boat; 160 by bicycle; and 385 by foot). Benton Basham, in 1983, topped that with a total of 710. 1987 marked the second time that there was a competition during a single year, with Steve Perry ending up with 711 and Sandy Komito setting a new standard with 721. In 1992 Bill Rydell made a serious attempt at the record and ended with 714 species for the year.

Big year competitors of 1998 were the subject of a book, The Big Year, by Mark Obmascik. Three birders, Sandy Komito, Al Levantin, and Greg Miller, chased Komito’s prior record of 721 birds. In the end Komito kept the record, listing 745 species[2] birds plus 3 submitted in 1998 and later accepted by state committees for a revised total of 748.[3] The book was adapted for the 2011 20th Century Fox film The Big Year.

In 2005, Lynn Barber did a big year in the state of Texas and saw a record 522 bird species. In 2008, she did a big year in the ABA area (see above) and finished with 723 bird species.[4]

Starting in the summer of 2007, teenager Malkolm Boothroyd and his parents, Ken Madsen and Wendy Boothroyd, attempted a big year without the use of fossil fuels by planning to bicycle over 10,000 miles to get over 400 species for the year.[5] They started in their home province of the Yukon Territory, rode down the Pacific Coast, looping back around Arkansas to catch the Texas spring migration, then eastward to Florida. They dubbed this attempt a “bird year,” rather than a big year. In the end, they covered more than 13,000 miles by bicycle and tallied 548 species, raising more than $25,000 for bird conservation in the process.

In 2010, Chapel Hill, North Carolina birder Chris Hitt set out to try to find as many different species of birds as he could in the lower 48 states (excluding Alaska, Hawaii, and the country of Canada) while enjoying good food and the company of friends. He became the first birder to see 700+ species in the lower 48 in a single year, finishing with 704.[6] In the same year, Virginia birder Bob Ake generated the second highest total for a continental big year, ending the year with 731 species, an extraordinary total achieved without the benefit of the relatively unique weather effects of 1998.[7] Also in 2010, John Spahr finished his ABA area big year with 704 species.

The highest total for a mixed gender couple was also in 2010, Claire Spengler and Kyle Martin; who combined for 728 species. The couple spotted a majority of their birds in the Northeast United States.

In 2011, Colorado birder John Vanderpoel set out to complete a big year and had spotted over 700 species before November. Vanderpoel was considered a threat to Sandy Komito’s big year record of 745 species, and was reportedly the fastest birder on record to reach 700 species in a year. However, ultimately John only managed 744 birds, missing out on the record by 1.[8]

Published big year books

- Wild America (1955) by Roger Tory Peterson & James Fisher

- Call Collect, Ask for Birdman (1980) by James M. Vardaman

- Looking for the Wild (1986) by Lyn Hancock

- The Loonatic Journals (1987) by Steven Perry

- Birding’s Indiana Jones: A Chaser’s Diary (1990) by Sandy Komito

- The Feather Quest (1992) by Pete Dunne

- A Year for the Birds (1995) by William B. Rydell, Jr.

- Kingbird Highway: The Story of a Natural Obsession That Got a Little Out of Hand (1997) by Kenn Kaufman

- I Came, I Saw, I Counted (1999) by Sandy Komito

- Chasing Birds Across Texas: A Birding Big Year (2003) by Mark T. Adams

- The Big Year: A Tale of Man, Nature, and Fowl Obsession (2004) by Mark Obmascik (later the basis for a 2011 comedy film distributed by 20th Century Fox)

- Return to Wild America: A Yearlong Search for the Continent’s Natural Soul (2005) by Scott Weidensaul

- The Big Twitch (2005) by Sean Dooley (an Australian “Big Year”)

- The Biggest Twitch: Around the World in 4,000 Birds (2010) by Alan Davies and Ruth Miller

- Extreme Birder: One Woman’s Big Year (2011) by Lynn E. Barber

References

- ^ Kaufman, Kenn: Kingbird Highway: The Story of a Natural Obsession That Got a Little Out of Hand; Boston, Houghton Mifflin Co., 1997, p. 16.

- ^ http://www.surfbirds.com/Features/Attu.html

- ^ http://www.nabirding.com/2011/11/08/interview-with-sandy-komito-745-or-748/

- ^ Barber, Lynn (2011). Extreme Birder: One Woman’s Big Year. Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-1-60344-261-9.

- ^ Stewart, Ian. “A big green year for the birds”. Yukon News. Retrieved 8 December 2011.

- ^ Slow Birding: the big year meets the big night

- ^ Bob’s Birds and Things

- ^ Atlantic Monthly October, 2011