Author Archives: Richard

Increase in bird song activity later in the nesting season.

Written by Norm Famous on maine-birds@googlegroups.com

I first experienced a rise in bird song activity while mapping the distribution of breeding bird species inside 20-acre blocks of forest. Song or territorial activity for the early nesting species that arrive inApril and early May such as white-throated sparrows, juncos, hermit thrushes and winter wrens are likely birds bringing off a second clutch, or renesting pairs whose first attempt was unsuccessful. In general, this increase can occur in both mid-June as well as July since there are two different nesting attempts involved.

Song production from species that winter in the tropics (Neotropical migrants) whose populations typically arrive in May through early June (mostly from mid-May onward), slows down after territories are firmly established and birds are well into incubation and gathering food for nestlings.

In early July when Neotropical migrants begin to fledge, the broods wander out of their parent’s territories into neighboring territories. That seems to result in an increase in song activity.

Periods of cold weather in June may result in higher nest mortality causing renesting later in June and early July. This adds to the increased song activity. I experienced this about ten years ago after a very cold and damp June in the form of a large increase in dependent young black-throated green warblers, American redstarts, blue-headed vireos and magnolia warblers throughout August. At the time, I was conducting fall migration counts every 10 days from August 1 through October.

Unmated males, by contrast, and birds attempting to renest during this period will sing vigorously in mid June. Unmated or wandering males are easy to detect when you have all the established breeding territories delineated or mapped and extra singing males show up and wander through the plot for one to several days. It is kind of fun to witness as the established males react, sometimes coming over from one to two territories away.

To summarize, the answer is not simple but after the mid-June lull of bird song activity, the increase is due to a combination of renesting attempts, the breakdown of territory boundaries by wandering broods and unmated wandering males. I am sure there are contribution physiological factors and other causes, some species-specific.*On another note!*

In regards to new unmated wandering males of the same species interring a territories (that is, new birds singing unfamiliar song renditions to the local population), you get a similar reaction when using song playbacks to lure target species into view.

*This practice can cause chaos to the entire local breeding population to both the target species as well as related species.*

I was working on an experiment at Bass Harbor Head on MDI where I was attempting to evaluate if warblers nesting in spruce-fir forest would react to playbacks of songs from other co-habiting warbler species when played in close proximity high in the canopy (e.g., within 40 feet). I attempted this work in response to studies that established that there was a ‘pecking order’ among the some of the spruce woods nesting warblers (the diminutive northern parula was at the bottom).

I suspended speakers 35-40 feet into the canopy (on light aluminum poles with a wire running down to a small amplifier) and played songs of a different species when I had a target male in view.

*Well, all ‘hell’ would break out in the middle to upper canopy. *The target male often looked toward the speaker and pauses or stops singing. However, neighboring males of the playback species went crazy and charged the speaker and chased any nearby birds regardless of species (again mostly warblers and golden-crowned kinglets). Within a half a minute or so, males of the playback species from neighboring territories charged into the ruckus and started chasing one another. I only played 3 to 5 (max) song renditions to the target species). If there was going to be a reaction, I expected it to be instantaneous.

*How large can the disturbances caused by playbacks be?*

Birds from up to three territories away joined the activity (some greater than 100 meters away). From the perspective of the study, this was extremely frustrating because it took over a half hour to assemble the pole segments and raise them through an opening in the canopy before having to wait for a target bird to come into view; the combined time usually exceeded an hour.

Once the local bird population was disturbed, you could not repeat the experiment at that location with 1/4 mile. Moreover, disturbances sometimes extended beyond a half hour (both inter and intra-specific chasing).

Needless to say, I did not gather enough information to address the original question about interspecific territoriality among birds within the same feeding guild, which at this location was comprised of 7 to 9 species of high- and mid-canopy insectivorous foliage gleaners (say that three times in a row).

*What are the implications regarding using playbacks during the nesting season? *

*Using playbacks will create chaos within the local breeding population of both the target species and other species, at least within the same size and taxonomic groups. I cannot speak to interactions beyond these warblers and kinglets. However, bird song is the standard form of mate selection and territory establishment and defense. *

*What happens when there is chaos? *

Birds are more susceptible to predation because their attention is elsewhere.

Birds were flying through and above the canopy for extended periods of time. They waste energy.

If the weather is marginal or the foliage very wet, females drawn to the commotion leave nests exposed or fledglings (think of toddlers) follow adults into the action and are more susceptible to predation.

Think about this the next time you use playbacks during the nesting season. The species that you are broadcasting often contain songs of other species. The temptation to use playbacks increases when the woods are quiet in the afternoon or during bad weather. On a more upbeat note, other than increased vulnerability to predation, the energetic and weather related risks appear less during the migrations.

When casually using playbacks, these disturbances are not typically apparent. I have no reason to suspect that this does not happen. However, when you know the locations or distribution of most the territories of all species in a local population, you can observe the chain of reactions.

I have to remember this when I am tempted to use playbacks to attract a species. I used playbacks while surveying a local population of Bicknell’s thrush along a logging road and observed the chaos among both Bicknell’s thrushes and Swainson’s thrushes. I followed singing and calling Bicknell’s thrushes from over 150 meters away work their way over to the disturbance caused by the playbacks. I did not pay attention of other species in the vicinity. In retrospect, I had forgotten about the study described above.

*Be cautious!*

*

*

*Birds are great!*

*

—

Norman Famous, Wetlands and Wildlife Ecologist

513 Eight Rod Road

Augusta, ME 04330

(207) 623 6072

Brown Thrasher – Undercover Expert

Brown Thrasher – Undercover Expert by Sue McGrath

The Brown Thrasher is an actor, robed in reddish hue, not in the distinguished gray like the catbird or the mockingbird. As noted in Chris Leahy’s information packed and engaging resource, The Birdwatchers’ Companion, the Brown Thrasher doesn’t beat or thrash with its long tail and doesn’t thresh with its long, curved blade of a bill. The bill allows it to forage deep in thickets and last season’s leaf litter by sweeping the detritus and soil away and then pecking, probing and seeking insects, snails, toads, frogs, seed, beetles, fruits and nuts.

I watch them intently as they pass in jerky flight along the vegetated edges roadside and take cover. The ruddy hue makes them difficult to see undercover.

I smile when I hear their smack call which I liken to a loud kiss ~ that “tcheh” call note of this mimic. I regularly focus on Brown Thrashers as they cross low over the road at Parker River National Wildlife Refuge. My concern for them heightens when the beach-goers stream to the Refuge’s and Sandy Point’s beaches. I’ve studied them for hours as they fly in and out of the shadbush, serviceberry, shadblow, viburnam and beach plum thickets at this important and renowned birding area. They appear unsettled and uncomfortable in the open; they’re in their element when undercover.

The Brown Thrasher has several monikers: Brown Thrush, Eastern Roadrunner, Sandy

Mocker, Ferruginous Mockingbird, Planting Bird and Red Mavis.

The Brown Thrasher has a slender bill, and the lower mandible has yellow at the base. Its face is gray; its eyes are yellow. Those white wing bars and yellow legs are easy to discern and focus on. Its tail is long, rounded and keel-like. It’s known as a large, boldly patterned, long-tailed skulker that loves the thickets. Both sexes are rich,bright rufous with buff to white underparts with black streaking. The Brown Thrashers are conspicuous due to their large size [9-12 inches]. With a wingspan of 11-13 inches, they are seen well as they dart low, barely undulating, in front of my car. I’ve invested time watching them dust bathe roadside when I’m heading to Sandy Point.

The male Brown Thrasher’s rich, musical and varied song is one of duplicity, a series of long phrases separated by pauses. This mimic has a large song repertoire and is the only thrasher routinely seen in the northeast.

By the second or third week in April, the males arrive. Once on territory, the vain male will perch high vertically and announce the breeding season. The male is on territory ahead of the female, and often his song is delayed for a few days. When the female arrives, the male’s song of doubleness begins. Once a mate is secured, the pair limit their movements and begin nest building. The mated male sings a softer song. The female shapes the nest, and both male and female bring in the nest

construction supplies – twigs, grapevine, rootlets, grass and dry leaves. The nest is a hefty, dense parfait with many tiers – often four – first twigs, then dry leaves, grapevine and paper compose the second tier; the third tier is stems, twig roots with soil, and the fourth tier is rootlets without any dirt attached. I’ve watched them beat the roots on the hot, black pavement and shake them to remove the dirt. The nest’s outside diameter measures 12 inches; the inside diameter is 3 – 4 inches; the inside depth is 1 inch.

Often the nests are in thorny shrubs below 12 feet; but most often they are at 2 – 7 feet. I found an active nest on the ground once. 2 – 6 eggs are laid that are white to pale blue with faint to heavy speckles and muddy brown markings. The Brown Thrasher is aggressive around the nest like a highly-skilled defenseman on the “Atlanta Thrashers”…

The nestlings are helpless with downy tufts; they fledge between 10 to 14 days, earlier than Gray Catbirds and Northern Mockingbirds. The male has charge of the fledglings, affording the female the opportunity to produce 2 – 3 clutches. If there isn’t a second or third brood, the pair divide the care of the fledglings, sometimes moving the young to separate areas.

Article is from the June Newburyport Birders Newsletter

Image by ibm4381

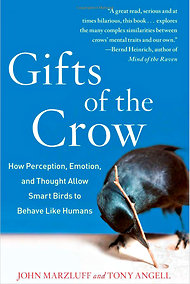

Gifts of the Crow

The Games Crows Play, and Other Winged Tales

By JAMES GORMAN

Published: June 11, 2012 in New York Times

Snowy Owl Season in Massachusetts

- Here is a summary of the Snowy Owl season compiled by Norm Smith of Massachusetts Audubon.

- The snowy owl season for this year from November 2011 through May

2012 was a great one. We banded a total of 52 snowy owls and

recaptured an owl we had banded two years ago. Of the owls banded 42

were captured at Logan Airport, 29 were released at Duxbury Beach and

13 released at Plum Island. In addition to the owls banded at Logan

Airport 4 owls were banded at Duxbury Beach and 6 were banded at Plum

Island.

All the 53 owls captured were in great condition, good body weight

and excellent feather condition. 46 of the owls were hatch year birds

(Owls that were born last summer) and 7 were after hatch year birds

(owls more than 1 year old). There were five snowy owls found dead

this season in Massachusetts, 1 hit by a propeller of a Cape Air

plane at Logan, 1 killed by a jet blast at Logan, 1 found dead on

Deer Island that died from rodenticide poison, 1 found dead at Plum

Island that had a broken wing and 1 found dead at Plum Island that

had a pellet stuck in its throat from the teeth on the lower jaw of a

rat that had perforated the esophagus and the owl could not

regurgitate the pellet and died.

- The last 2 owls that were captured at Logan were released at Plum

Island on May 11th and May 29th.

From communication with researchers on Baffin Island over the years

when they have a good lemming year like last summer the owls breed

producing lots of young and that is when we see good owl numbers in

Massachusetts. If in fact these owls were leaving the arctic because

there was no food in the arctic they would probably never make it

here and if they did would not arrive here in good condition.

Over the past 31 years that we have been doing research on snowy owls

the best winter to date was the winter of 1986-87 when we banded 43

snowy owls at Logan Airport. This past winter was the second best

with 42 banded at Logan.

Thanks to the Nuttall Ornithological Club we were able to put a

satellite transmitter on one of the owls to track its movements.

Check out our web site to track this owl.

http://www.massaudubon.org/Birds_and_Birding/snowyowl/index.php

Norman Smith

Sanctuary Director

Mass Audubon Blue Hills Sanctuary

1904 Canton Ave.

Milton, MA 02186

617 333-0690 ext 222

nsmith AT massaudubon.org

Birding by the Dredging Containment Site

I’ve been birding in Maryland for a few days with my grandson, Dane, and seeing a nice array of mid-Atlantic birds. Today, we drove up to the Swan Creek/Cox Creek Impoundment area outside of Baltimore to look for a Red Phalarope that had been reported yesterday — and dipped on it but had a great time.

I am part of a local FB group, the Anne Arundel Birding & Bird Club, and they kindly sent me directions and procedures to follow at the site. This place is crazy — nestled between a chemical plant and a power plant, it has large diked areas for material dredged from Baltimore Harbor.

It’s an active site with trucks, large backhoes, and assorted machinery working away while birders aim their scopes at the containment lagoons. Some forward-thinking folks worked out an arrangement that keeps over a 100 acres in a conservation easement and a lot of restoration work and replanting has been done — and birds love it: over 160 species have been spotted there. There’s a lot of debris and funky looking liquids but like many landfills and wastewater lagoons, it’s a great place to bird.

We showed up and signed in at the office and met a couple of birders who told us that no one had seen the Phalarope – that many of the “big guns” were there early with no luck. (Early arriving construction workers reportedly flushed it.) Still, looking at the ponds and then walking down to some reclaimed wetland, we did fine. A Little Blue Heron flew right over us giving us good looks. (It’s great when Dane can see stuff without fiddling with bins.)

| Little Blue Herons nest on the property. |

I was on the lookout for an Orchard Oriole since I needed one for my life list and they had been reported by many birders over the last few days. Just as a new acquaintance, Matt Grey, was giving me the details on Orchard vs Baltimore Orioles, we saw several and got some wonderful looks through the scope. Of course, Dane comes to my chest so we have a fun time adjusting the telescope but he saw it well.

|

| An Orchard Oriole was a life bird for me. |

We saw some other good birds: A diving Least Tern (another lifer), a couple of Snowy Egrets, a Belted Kingfisher, an Indigo Bunting, and others. Returning to the ponds at the starting point, we scanned one last time and through the shimmer, picked out a Black Bellied Plover on the far shore.

Adirondack Birding – The Barn Swallow

Coinciding with the onset of bug season in the Adirondacks is the return of our insect eating birds. While nearly all of these perching birds have an attractive musical call that announces their presence, most maintain a secretive routine so they are rarely spotted.

The swallows are the most visible bug consumers as their preference for perching in exposed places and feeding over open settings allows these skilled aerialists to be regularly seen.

Additionally, their habit of placing their nest close to human dwellings and in plain view of any passerby makes them well known to residents and visitors of the Park. Among the various species of swallows that come to the Adirondacks to » Continue Reading.

Who Put Those Dents In Back?

I have not blogged about my encounter with a Texas tree, which must have moved behind me as I backed up, but to make a long story short, I was in a hurry to get going from Falcon State Park. We had emptied tanks and the layout forces you to turn around to leave the park. I thought we were clear and as I backed up (not having asked Mary to help) I heard sort of a crack of a branch. Just thought it was brush I’d backed over so I pulled ahead, backed up and heard it again. And off we went toward Corpus Christi.

After an hour or two, we stopped for fuel and as I approached the trailer from the rear, this is what I saw.

It didn’t make my day. I was sure there were no trees back there, they must have moved!

We had an insurance person take a look at it before we came home but now it is time to deal with the dents. So, the other day, I hooked up the Airstream and we drove over to see one of the experts in Airstream restoration, Colin Hyde.

Colin, well-known for his renovation work, is located across Lake Champlain, about two hours away. The day didn’t start well — I again had trouble with the electronic jack that raises the front of the trailer. I tinkered with that and soon we were heading toward Burlington on I-89. It made us think of the last time we had done that — just four months ago, when the weather was similar with low clouds and spitting precipitation, but the temperature was about 30 degrees colder.

Getting to Plattsburgh involves either driving up to Rouses Point and way back down the Northway, or taking the ferry. I’d never used the Grand Isle ferry with the trailer but it was a piece of cake. Colin’s operation was just down the road and soon, he was looking things over.

The problem with having an expert look at your used trailer is that he sees everything — the problems with the floor, the inoperative break-away switch, the leaky vent — I came home with quite a laundry list. Don’t get me wrong, it’s great to have sharp eyes helping and Colin is very good at separating “nice-to-do” items from critical ones.

Colin’s business is booming and I’m going to try to shoe-horn our project into his busy work schedule. We brought the trailer back and while he is ordering parts and scheduling the work, I’ll take a stab a disassembling some of the cabinetry and other items needing to be removed before his work begins. It’ going to be a hassle but who can I blame but myself. Trust me, I’m much more cautious with my backing up and now always ask Mary to help me out.

Chasing The White Bird

Yesterday morning I drove up to Berlin Pond, a favorite local birding site, and immediately noticed several larger birds moving with the Tree Swallows over the water. One was graceful, black-bodied, and flew down to the water seemingly to grab insects. It was a Black Tern — the first one I’ve seen.

The light mist made camera-work tough and I almost ignored the white Tern that seemed to be flying near it. I’m not great at identifying terns and thought that it was a Common Tern.

Moving around the pond in the truck, I noted Common Loons, ducks, geese, a Bald Eagle and then ran into two birder friends who were all excited about the white Tern. They had only a quick look and thought that it had characteristics of an Arctic Tern. So, the hunt was on. Cellphones passed the news of this probable and we spent an hour or two looking for it, with no luck.

Meanwhile, as we waited, a Green Heron did a close fly-by, circled, and landed not far away, posing for this digiscoped picture. What a neat bird — we hope they might be nesting nearby.

A Couple of Life Birds

Like many birders, I subscribe to listserves for areas where I plan to travel and “lurk” on them, checking out what others are reporting in the days and weeks prior to my arrival. Thus, I was reading MASSBIRDS prior to our grandparenting trip and noting that folks were seeing some neat birds at the Salt Pannes south of Newburyport on Route 1A. I drove over the first morning after we arrived, to find several birders already in place with scopes aimed at the marshes.

As it turns out, it was the week prior to the MA Audubon’s Bird-a-Thon which is this coming weekend so birders were out in force scouting. For Bird-a-thon 2012, there are 28 teams, each supporting an individual wildlife sanctuary, a group of sanctuaries, or a Mass Audubon program. The teams are vying to see:

- Which team can spot the most bird species in 24 hours

- Which team can raise the most money for their wildlife sanctuary or program

This was a long-legged wader a little smaller than the nearby lesser yellowlegs, with a noticeable white supercilium and a fairly long bill. I couldn’t see any droop at the tip of the bill on this bird, or any color on the face yet, as it was apparently just beginning to come into alternate plumage. What clinched the ID was its behavior: bill held very vertically, the bird doing some pecking but also showing the sewing-machine-like drilling with the head underwater that is virtually unique to this species among the larger sandpipers (much faster drilling than dowitchers, whose motion reminds me of an oil derrick rather than a sewing machine).

|

| A Stilt Sandpiper in front of a Greater Yellowlegs. |

|

| Yellowlegs departs while Stilt Sandpiper keeps feeding |

We saw a flight of Glossy Ibises but could not spot the earlier-reported White-faced Ibis among them. Then, from stage left, paddled a group of Wilson’s Phalaropes which also had be reported, and were also a life bird for me. I got some poor quality photos for the record but the camera auto focused on grass in the foreground and the images were blurred.

Other birds there included Mallards and Green-winged Teal, Willets, and a Solitary Sandpiper or two. My new birder acquaintances all were hoping that the birds would hang around for the Bird-a-thon but who knows, it’s migration time.